Bruce Meredith, Inc.

DC History

Fort Stevens – A Washington, D.C. Story

This is the story of a ragged few volunteer warriors in 1864 and the most valuable real estate in Washington, D.C. – the United States Capitol Building. A group of tenacious citizens repulsed the third Confederate invasion of the North during the Civil War. They saved the Capitol Building, Washington, D.C. and the Union.

VIGILANCE AND COOL THWART THE 1864 CONFEDERATE INVASION OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

by Bruce Meredith

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA – THE MOST FORTIFIED CITY IN THE WORLD

In 1861, after suffering a shocking defeat at the Battle of Bull Run across the Potomac River from Washington, the Union urgently turned its attention to providing protection for the Capital. It built 68 enclosed earthen fortifications on the high ground around the city’s perimeter and across the river in Virginia. By 1863 the Union had connected these forts with nearly impenetrable fortifications. They included 20 miles of rifle men’s ditches and 32 miles of roads. General George B. McClellan stationed 23,000 regular troops in Washington to man the forts and protect the city. it became “the the most fortified city in the world.” Military Road today is a prominent road crossing the northern part of the city. Originally it gave connecting support to the city’s forts.

GENERAL LEE PLANS THE INVASION OF WASHINGTON

In 1864 General Ulysses S. Grant decided to move the troops protecting the nation’s Capital to help with the Union siege of Petersburg, Virginia. General Robert E. Lee saw an opportunity in this relocation of Union troops. In a bold and imaginative move, he dispatched Lieutenant General Jubal Early north through the Shenandoah Valley with a force of over 20,000. Early’s mission was to ensure the security of the farmland in the Valley, an important bread basket for the Confederacy. It was also intended to menace Baltimore and Washington.

A strike at the vulnerable, now unprotected city of Washington would be a huge success. Washington was the home of government. It was the national symbol of the Union. It had been 50 years since the British army stormed the Maryland countryside, torched Washington and plundered the White House and the Nation’s Capitol Building.

Rebel invasions had been rebuffed at Antietam and Gettysburg. In 1864 even a short-lived Confederate victory in Washington could have stunning results for the outcome of the war and for the conditions of the peace settlement. Good military intelligence was at a premium. Grant for a while gave little credence to vague reports that Early was moving such a large force out of Lynchburg where they were garrisoned.

Of immediate concern to Lee was Grant’s punishing siege of Petersburg and Richmond. The mere presence of Early’s force north of Washington would surely cause Grant to pull a large part of his force from Petersburg to secure Washington. A successful Confederate invasion of Washington would extend the military stalemate in the war.

It also would give the “Peace Democrats” and “Republican Radicals” fuel for pressing for immediate peace negotiations. It would virtually doom Lincoln’s fate in his upcoming re-election. The public in the north was unhappy with the war. Former General George B. McClellan, the president’s opponent in the election, was promising to make peace with the South.

MONOCACY – THE BATTLE THAT HELPED SAVE WASHINGTON

Major General Lew Wallace, stationed in Baltimore, acted immediately on reports from railroad officials that Early’s troops had crossed the Potomac. They were headed south from Frederick toward Rockville, Maryland. Wallace led his much smaller force to confront Early at Monocacy River. Wallace lost the battle, but with careful planning and stout resistance succeeded in costing the Confederates 900 casualties. Crucially he also delayed Early’s planned invasion of Washington for a day. Historians generally regard the Battle of Monocacy as the only decisive victory during all the Confederate invasions of the north. They also agree that it was Wallace’s valiant stand that helped save Washington.

Wallace sent an urgent message about the crisis to Grant. Grant now quickly responded to Early’s attack. He sent two divisions of his battle-seasoned VI Corps north. One group traveled on steamboats up the Potomac River under General Horatio G. Wright. General Frank Wheaton took another group north by train.

That very day Early’s cavalry was reconnoitering Fort Reno, which was located directly in his path down Rockville Pike and Wisconsin Avenue into the city. Early learned that Fort Reno was well equipped with heavy weapons. He altered course and moved east. His new plan was to go down the 7th Avenue Pike (now Georgia Avenue) through Fort Stevens into the city.

Wright’s VI Corps began to disembark that same afternoon at Washington’s 6th Street Wharf “amid a tumult of joyous cheering.” Lincoln urged them on as they marched directly up the 7th Street Pike to block Early’s invasion of the city at Fort Stevens.

AND LINCOLN SAID, “BE VIGILANT, BUT KEEP COOL”

President Lincoln advised “the enemy is moving on Washington. Let us be vigilant, but keep cool.” What followed was an amazing story of vigilance, resourcefulness, courage, and surprising cool as the city prepared to defend itself. A wounded cavalryman recuperating in a hospital in Washington, Major William Fry, visited other hospitals in the city to recruit a force of about 500 cavalrymen. He also found them mounts. This troupe moved north out Rockville Pike to scout and engage Early’s lead forces on July 10 as they advanced to the south.

The Veteran Reserve Corps – To man Fort Stevens for the coming onslaught, the “Veteran Reserve Corps” was recruited. This force was comprised of older veterans, many of whom had not seen military service for decades since the Mexican War. Supporting these veterans were convalescing wounded soldiers, and clerks from the War, Navy, and State Departments who were issued muskets. Joining them were recruits who had enlisted with the Union Army to serve for 100 days as temporary rear-echelon troops.

ONE DAY

Beginning of the Fort Steven’s Battle – Early’s lead elements had arrived at the breastworks of Fort Stevens around mid-afternoon on July 11. They actively probed and calibrated the scope and fighting caliber of the Fort’s defenders. The small Veteran Reserve Corps showed surprising resistance with fort cannons and musketry. The volunteers even managed to block Early’s efforts to bypass Fort Stevens through what is now Rock Creek Park.

Early was eager to chalk up a triumphant victory to round off his month-long campaign. He needed a win that would significantly strengthen the Confederacy’s position in the war. He also wanted a crowning conquest that would launch him into the circle of legends with his predecessor, General Stonewall Jackson.

Early wanted to storm Fort Stevens and sweep into the city with a vigorous mighty wave of destruction. As the day wore on, however, he saw his troops straggling in from a day long trek. They were fatigued from their four-week campaign, the battle at Monocacy, and their long, gruelling march in the blistering heat. Early determined that his men were “completely exhausted and not in a condition to make an attack.” He decided to give them some rest and deferred his major assault by one day.

6th Corps Flags Flying Over the Parapets of Fort Stevens – The dawn of the next day, July 12, it became clear that the moment for Early to act had vanished. General Lee’s imaginative invasion gambit with all its incredible historical implications had failed. Looking through his binoculars that morning Early saw the unfinished Capitol dome just a few miles away. He also observed VI Corps flags flying over the parapets of Fort Stevens. In the trenches the shiny regalia of the Veteran Reserve Corps had been replaced by the battle-worn uniforms of the VI Corps. These troops were veterans of Fredericksburg, Antietam, Gettysburg, Wilderness, and Cold Harbor, some of the fiercest battles in the history of warfare.

Thousands of these hardened warriors under generals Wright and Wheaton had arrived at Fort Stevens late in the evening of July 11. Vulnerable and unprotected Washington was now bristling with devastating military force to support its resolute defiance. Early and his division commanders concluded that a major assault “would ensure the destruction of my whole force.” He continued his engagement on July 12 with only limited skirmishes. Then quickly he withdrew from Washington and crossed the Potomac River into Virginia.

THE BATTLE OF FORT STEVENS – A FEW THINGS TO REMEMBER

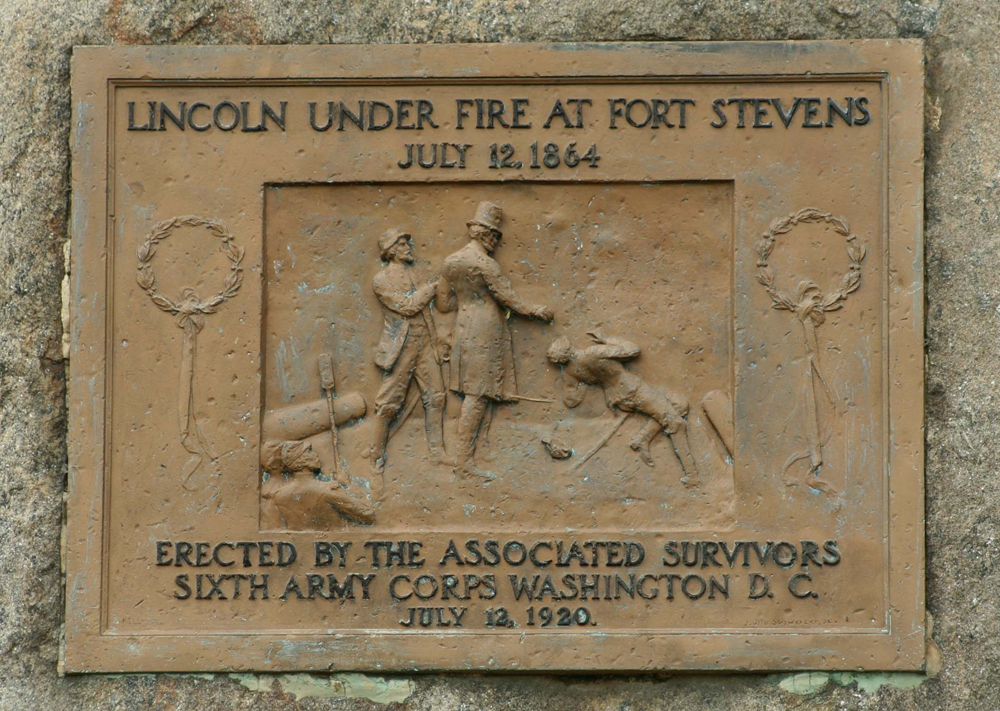

“Get Down, You Damn Fool!” – What is remembered most of those pivotal days in July 1864 in Washington? It is the image of towering six-foot-four-inch President Lincoln wearing his stovepipe hat. He is standing on the parapet of Fort Stevens to get a better view of the action. Bullets whizzed and hissed all around. He is the only President while in office to come under direct enemy fire in a battle. When a Confederate sharpshooter’s bullet struck the officer standing next to Lincoln, a voice called out, “Get down, you damn fool!” A plaque marks the spot on the parapet where Lincoln stood that day. Legend has it that the young officer calling out the warning was Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Washington and the Union Are Saved – The Battle of Fort Stevens was the only Civil War battle fought within the District of Columbia. In military terms it was relatively small in scope and duration compared to other Civil War clashes. In terms of overall military and political consequences, however, the significance of Early’s defeat at Fort Stevens was monumental. The stunning news of Confederate forces pillaging hapless Washington would have traveled on the wind. Washington was the logistical support center for Union Forces, the heartbeat and pride of the Union. Sacking Washington could have shortened the war and culminated in a negotiated peace that did not include the abolition of slavery. It was not to be.

Lincoln Leads the 6th Corps to the Battle at Fort Stevens – An indelible comment from Early to one of his officers closes out most short accounts of the Battle of Fort Stevens: “Major, we haven’t taken Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell.” What Early could not have seen was what Abe Lincoln did that day. The President rode his carriage from the White House down to the Sixth Street Wharf on the Potomac to greet Grant’s VI Corps as they arrived in steamboats. He ignored the warship waiting there to take him away to safety. Instead in his carriage he guided the troops up the 7th Street Pike past fleeing citizens and soldiers in stretchers all the way to Fort Stevens.

Forget Early’s words of an Abe Lincoln scared like hell. Rather, encase in crystal the picture history gives us. It is a tall, cool, and defiant Abe Lincoln, Commander in Chief of all Union forces. In his black suit and stovepipe hat, he is personally leading his army to the battlefront to strike the Rebel forces gathering there to ravage his city.

Reporters who spent time with Lincoln reported that he was primarily “scared” during the battle about only one thing. Would Union commanders fail to pursue a retreating Early? Lincoln’s commanders did let him down. They did not pursue. Early successfully escaped to the Shenandoah Valley. He preserved his fighting force and carried with him substantial military stores, supplies, and other plunder.

Grant, too, was distressed with this lost military opportunity. He sent General Philip Sheridan to deal with Early. In October 1864 Sheridan defeated Early at the Battle of Cedar Creek, a key military victory that helped Lincoln win his November election.

General Lew Wallace, who so effectively delayed Early’s forces at the Battle of Monocacy, went on to become Governor of the New Mexico Territory and author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), a best-selling novel that has been called “the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century.” Citizens of the little town of Leesborough located nearby the battle gave General Frank Wheaton a special honor. They changed the name of their city to Wheaton. Wheaton is now a major Maryland suburb of Washington.

“SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF OUR COMRADES WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN DEFENSE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITOL, JULY 12, 1864”

The most poignant testament of this battle is located just two blocks up Georgia Avenue from the fortifications themselves. In the late evening of July 12, 1864, President Lincoln dedicated as hallowed ground a one-acre apple orchard, and named it the Battleground National Cemetery. It is one of the smallest of all our National Cemeteries. Of the 374 Union casualties suffered during the two-day battle, 59 died. The graves of the 41 who are buried at the Cemetery are arranged in two close rings around the center of the plot. Granite pillars mark the four New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania regiments of the fallen Union soldiers. One is etched with the words, “Sacred to the memory of our comrades who gave their lives in defense of the National Capitol, July 12, 1864.” A bronze plaque mounted on the side of the caretaker’s lodge holds the Gettysburg Address. A few markers arranged beyond the gravestones carry these lines from Theodore O’Hara’s poem for those fallen in battle:

The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat

The soldier’s last tattoo;

No more on life’s parade shall meet,

That brave and fallen few.

On Fame’s eternal camping-ground,

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards, with solemn round,

The bivouac of the dead.

Two smoothbore, six-pounder Civil War vintage cannons stand guard at the entrance to this eternal campground. These six-pounders give notice to a moment in our history that commands awareness and deep personal respect. Their presence stirs up the nearly forgotten but epic story of the Battle of Fort Stevens.

It is an amazing story of a small, vigilant gaggle of untrained but surprisingly resourceful, gallant and cool Union defenders. When their President told them “the enemy is coming” to their city, they went to Fort Stevens to meet him head on. There they confronted General Jubal Early’s overwhelming battle-hardened Confederate invasion forces. They fought, resisted, and died just long enough. They saved the Nation’s Capitol from being sacked that day. They thwarted General Lee’s invasion plan. They erased from history its staggering implications for the course of the war and American history.